The Menu West Papua Never Asked For

Food News from Indonesia | How gastrocolonialism replaces West Papuan food with rice and instant noodles.

Halo and welcome to Kepayang’s second edition of Food News from Indonesia, where I’ll sum up what’s been happening with our food scene in the last six months, plus a generous amount of my opinion. Similar to last year’s edition, this time you will also have a new story every week throughout August. That’s right, it’s the Independence Month spirit.

To remind you, Indonesia is a huge country with thousands of islands and a skewed focus on Jawa and Bali. So, to keep things fair, I'll be highlighting food news from underrepresented regions. Last year, I rounded up news from the provinces of Aceh, Nusa Tenggara Timur and Sulawesi Utara, and Maluku.

This year, it’s time for the provinces of Lampung, Kalimantan Utara, and today, let’s talk about Papua & Papua Pegunungan. Enjoy the read!

Disclaimer: I am not Orang Asli Papua (Indigenous Papuan), and this essay does not claim to represent their voices or lived experiences. I write with respect for Indigenous Papuans, their knowledge, and their connection to land and culture.

Also: I’m not a journalist. I’m just a writer with a passion for food, some self-taught research skills (mostly from trips to the pasar and supermarket), and a desktop research proficiency. The information below comes from news sources I personally trust, and all opinions are entirely my own. Please take everything with a grain of salt, do your own research, and let me know if I’ve made a mistake.

Terminology Note: In this essay, "West Papua" is used to refer to the western portion of New Guinea that is part of Indonesia, not specifically to Provinsi Papua Barat (West Papua Province) alone. When discussing specific provinces, they are named explicitly in their Indonesian term (e.g. Papua Pegunungan).

The term gastrocolonialism might be foreign to some of us, but defining it can simply begin with looking at the two words that make it up. Referring to the Oxford dictionary, ‘colonialism’ is defined as “the practice by which a powerful country controls another country or other countries”, while gastro or ‘gastric’ is defined as “connected with the stomach”. Putting these two words together, one may guess that it is a form of colonialism, involving food or the stomach, being imposed by one country on another.

In practice, gastrocolonialism can also happen within a single country.

One of the earliest works that discusses the idea of gastrocolonialism was written by a Chamorro scholar, Craig Santos Perez, in his book review (2013) of Facing Hawaiʻi’s Future. He uses the term to describe how colonial power, in Hawai’i, controls what people eat. This happens in many ways, such as:

Restriction of Local Food Production: The US military occupies land and water, while multinational corporations push native communities away from farming and fishing.

Displacement of Food Knowledge: The educational system cut ties to traditional food knowledge, while the media promotes fast foods.

Imposed Dependence on Imports: Communities end up relying on cheap, unhealthy imported foods.

In Hawaiʻi, these changes disrupted local food systems and made people depend more on outside supplies, a pattern that unfortunately can also be seen in places like the Indonesian provinces of Papua and Papua Pegunungan.

In West Papua, gastrocolonialism has been done since, well, colonial days, and still continues until today.

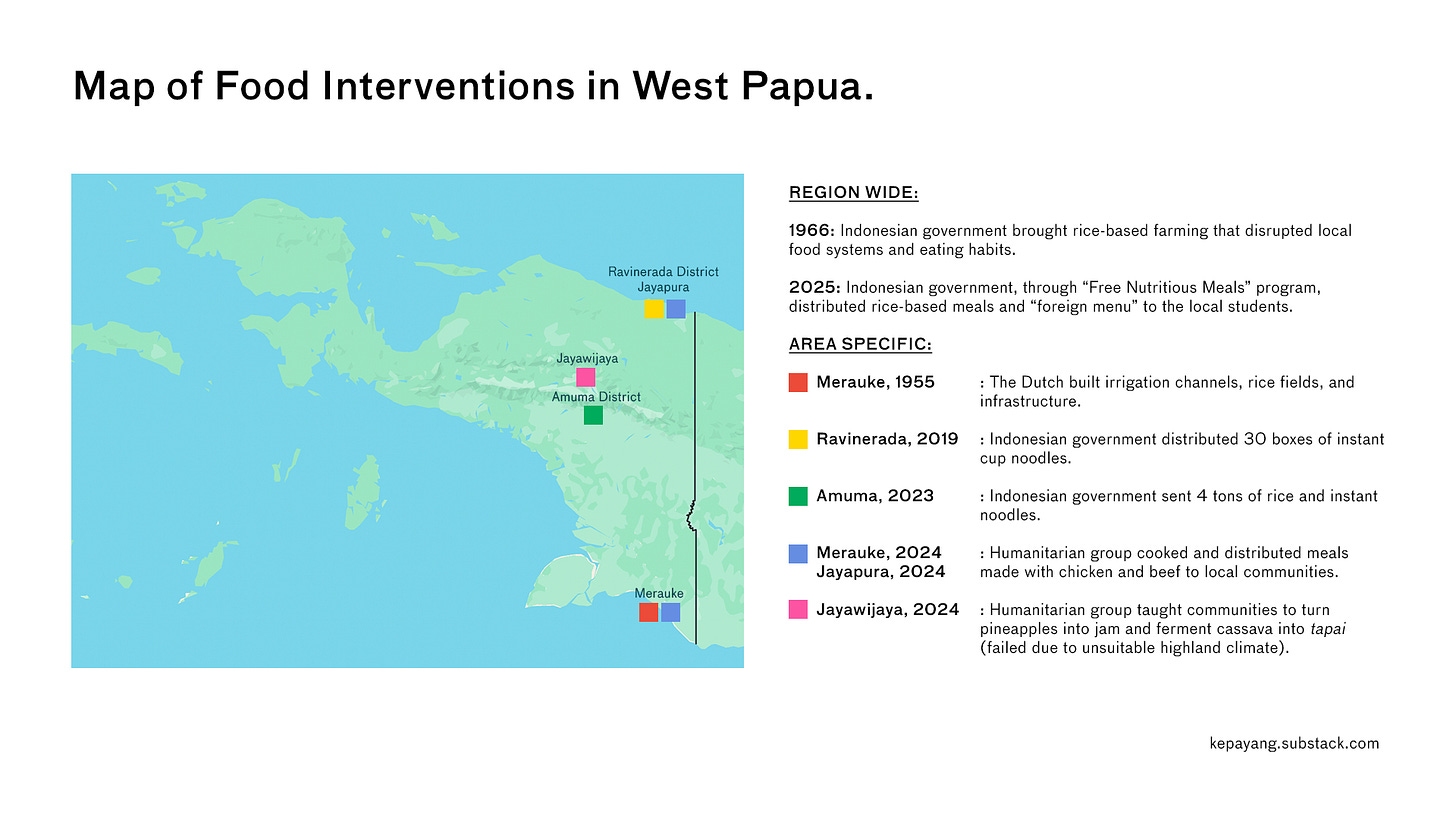

An early example of gastrocolonialism in West Papua, as noted by Arif and Yunus (2022), goes back to the Dutch colonial period, when Merauke, an area in southern West Papua, was turned into large-scale rice plantations. In 1955, the Dutch built irrigation channels, rice fields, and infrastructure, which continued under Indonesia through the transmigration program in 1966. The arrival of settlers from outside West Papua brought rice-based farming that disrupted local food, as well as shifted the local eating habits, by gradually replacing traditional West Papuan foods like sago and tubers with rice.

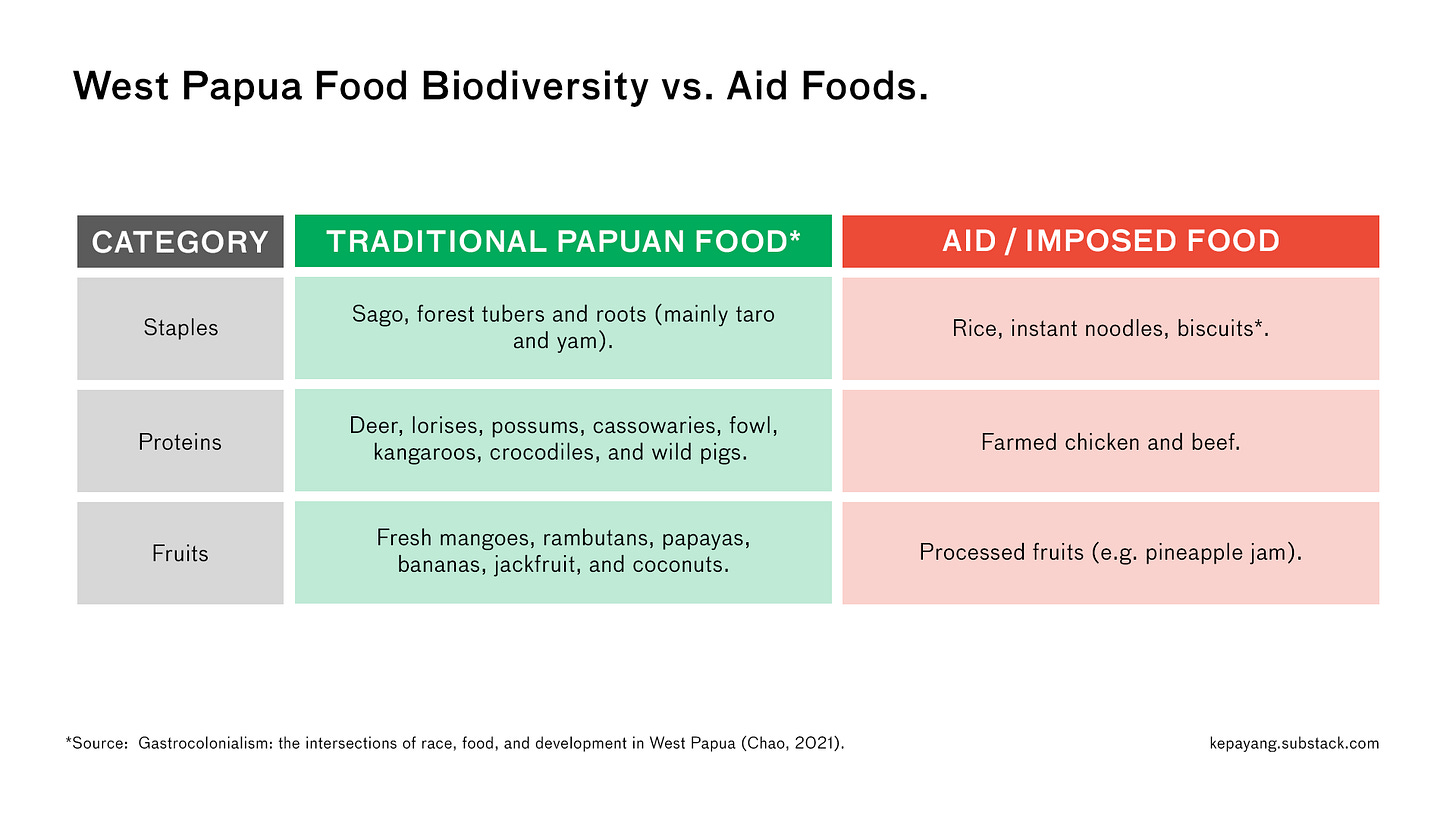

West Papua has an abundance, diverse, nutritious foods, and many communities share meaningful connections with them. Replacing these with uniform, instant options risks detaching people from their own food culture.

An article by Chao (2022) shows the wide variety of food West Papuan communities can find in the forest. From sago and tubers to forest game like deer and possums, and fruits like mangoes, papayas, and jackfruit. The article also shares how communities such as the Marind tribe see forest foods as more than just nourishment. They believe forest foods bring true satiety, especially “when eaten in the forest itself.” This example shows how deep the connection is between West Papuans, their land, and their food, something that instant meals could never replace.

However, government aid in West Papua has often come in the form of rice and instant noodles. During the 2019 floods in Ravinerada District, for example, the Indonesian government distributed thirty boxes of instant cup noodles. And in 2023, they again provided aid to Amuma District, this time sending four tons of rice and instant noodles.

To be fair, in cases like the ones above, sending instant food might have been necessary. But beyond emergencies, government officials often frame instant foods as a symbol of progress, something that supposedly allows West Papuans to “participate in the modern world” (Chao, 2022). That idea, of course, is far from the truth.

Kepayang is free for now, so any engagements mean so much to support the platform’s growth. You can subscribe to get the newsletter sent directly to your email, like, comment, and share if you resonate with what I write.

Alternatively, you can buy me a coffee through my PayPal here: https://paypal.me/chalafabia - or if you’re based in Indonesia, you can send your donation through QRIS here (under the name Tamanan). Any amounts are welcomed and will directly contribute to sustaining this platform to cover expenses related to operations, research, writing, and marketing. ☕️

This year, rice is still being imposed, through the government’s latest program, Makan Bergizi Gratis (Free Nutritious Meals).

Makan Bergizi Gratis is a program aimed at providing free nutritious meals to students across the country. In West Papua, however, these free meals are often rice-based, and, as langgam.id (2025) put it as “foreign menu to the local”.

According to researcher Pamungkas, quoted in Republika (2025), this raises some concerns. He explained that cases of hunger in West Papua are often linked to the introduction of rice, which led to cultural shifts and dependency. This is dangerous because, even though Papua has plenty of other food sources, people are pushed towards relying on rice, something that doesn’t naturally grow in West Papua. Government programs like this risk reinforcing that dependency.

I had a chance to chat with an elementary school teacher in Jayapura to get some insights from the school - let's call them Mawar (not their real name).

Mawar isn't originally from Papua, but they've been living in Jayapura for over 20 years and have been teaching for more than 10 years.

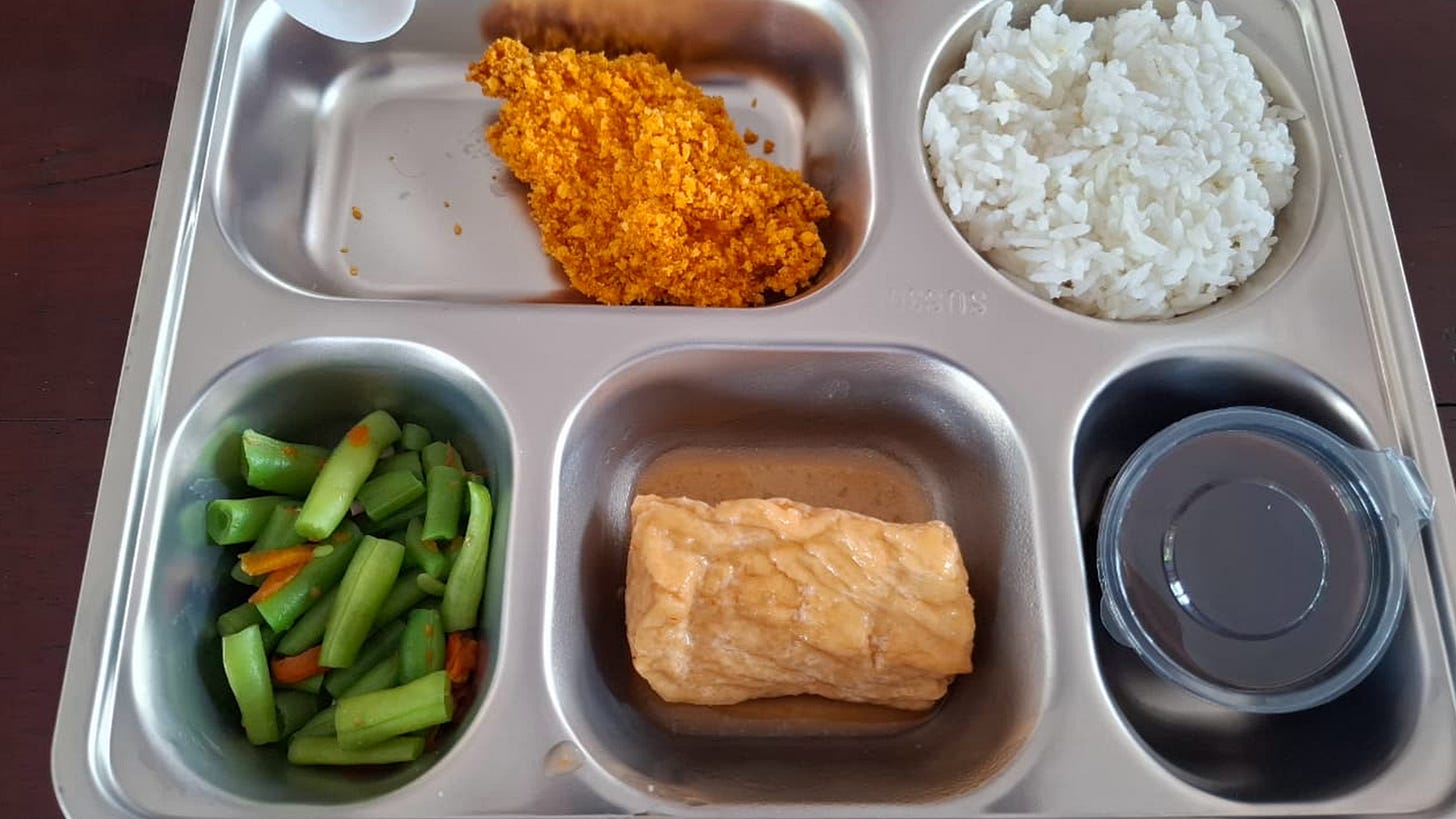

The free lunch was distributed to elementary students at their school. The food arrived around noon in stainless steel trays, and somehow, it was being handed out by uniformed police officers. I don't know if they're the best people to be distributing lunch to elementary kids, but OK, I guess?

Menu-wise, the food looked like it had decent portions and was nutritionally balanced, but Mawar shared that some things can be improved.

The first is food safety. "I was also sceptical about the menu they served to the kids. Even though it looked good, it might not have been safe to eat anymore", Mawar started explaining, because they found that some of the chickens were already spoiled.

“I immediately reported it to the SPPG (Nutrition Fulfilment Service Unit)", Mawar shared. They then add, "When packing the food, SPPG should let the temperature cool down a bit so it's not too hot. Otherwise, it spoils quickly." This case is not the first case that happened at schools in Jayapura.

Second is about the variety of food provided. Mawar feels the carb sources in the free lunch program could be evaluated. "I'd be more on board if, maybe, once in a while, the menu included native foods. Yes, there is rice. But we also have other native foods. And kids need to be educated to know and enjoy their native foods, too. With local foods, we can educate kids that there are other carb sources besides rice that can also meet our needs. Like taro or other tubers".

Mawar believed that involving other carb sources could help kids not be so dependent on rice.

"If everything has to be rice, then we'll think we can only survive by eating rice. We never know what the future will be like (especially) with climate change. There might come a time when it's really hard to get rice, but all we have is taro or cassava. If they're not introduced to these, that would be problematic", they shared.

Our conversation then concluded that the effort of introducing kids to native foods has to be done together by the schools, the government, and the parents, too. The reality is, many of Mawar's students still bring rice packed by their parents. "Parents nowadays think cooking native foods is a hassle. But the reality is that we have SO many options!", Mawar said. So to educate both parents and kids, at Mawar's school, they hold a communal eating event every three months. “It's potluck style, and we encourage bringing food made from native ingredients”, they shared.

I get it, cooking rice is kind of semi-instant. But I have to agree with Mawar on this. If this convenience ultimately creates distance between kids and native foods, is it even worth it?

Elementary schools are crucial for shaping children's relationship with food. Through communal meals, government lunch programs featuring native ingredients, and parents serving local foods at home, children can develop diverse palates, thus breaking dependency on rice.

Beyond government and institutional programmes, many humanitarian efforts also contribute to the same issue.

Over the past year, many have tried to help with food shortages in West Papua by giving out food and teaching food skills. In late 2024, one project became viral as they organised a cooking event, handing out meals made with chicken and beef to regional communities in Merauke (Papua Selatan province) and Jayapura (Papua province). Then, in early 2025, a different group taught another regional community in Jayawijaya (Papua Pegunungan province) how to process local crops, showing them how to turn pineapples into jam and ferment cassava into tapai.

Not mentioning names here. I intend to highlight the pattern rather than criticise individual efforts.

Whilst these efforts may stem from good intentions, they can subtly undermine local foodways.

To start, introducing external protein sources such as chicken and beef doesn’t align with Papuan hunting traditions. While meat consumption in urban areas such as Jayapura is more flexible and open to farmed meat (Mawar, 2025), according to the Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara (Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago) (2025), many regional communities in West Papua still have a strong hunting culture. Many regional communities eat meat only occasionally, and when they do hunt, it is with respect for the ecosystem by taking only what is needed. This highlights the disconnect between the said humanitarian efforts and West Papuan culture, where meat is obtained through balance and sufficiency, not through the commercial logic of farmed meat.

Similarly, teaching external food processing methods may send the message that indigenous techniques aren’t good enough. As FAO (2013) points out, it’s a mistake to start development from expert ideas while ignoring what local people already know. In West Papua, pushing foreign cooking styles without respecting indigenous traditions could weaken the food systems that have supported regional communities for generations.

It’s no surprise that the cassava tapai project eventually failed, perfectly illustrating this disconnect. The cold highland climate of Papua Pegunungan simply isn't suitable for that type of fermentation, something local food knowledge would have anticipated. The project initiator later acknowledged and apologised for this oversight.

From the Dutch era to today, West Papua has experienced decades of gastrocolonialism.

These food interventions follow the same pattern: whether through government programs or individual efforts, outsiders have consistently ignored the food practices that West Papuan communities already have. As a result, people often resist these efforts, become dependent on outside food, and projects fail.

Moving forward, any effort to help with food problems in West Papua must start not with outside assumptions, but through real conversations to understand what communities already have and what they actually need.

Other essays that I wrote recently:

🇮🇩 Read about why some Indonesians shop for their food in Malaysia: here.

🍠 Read about how cheap tapioca imports are hurting local farmers: here.

🍧 Read about my favourite, history-rich, iced drink: es teler: here.

🔥 Read about why cold savoury dishes are not a thing in Indonesia: here.

🌱 Read about the underrated Indonesian greens, ceciwis: here.

If you like today’s newsletter, please like and share it with your friends! Comment down below your thoughts, and let me know if you have any other topics you want me to discuss. Until then, I’ll see you next week!

Follow me everywhere:

TikTok: @berusahavegan

Kepayang’s Instagram: @readkepayang

Instagram: @menggemaskan

LinkedIn: Chalafabia Haris

Work with me: readkepayang@gmail.com

I know that the comment comes across as a double-edged sword, but how do we know that the indigenous diet doesn't malnourush them? It's good for the locals in the mountains to keep their diet from the plants around them, but there have been known cases of goitre in areas where access to iodine is scarce.

If they rely on root crops and ambuyat / papeda for carbohydrates and natural disasters strike, then rice would solve it. Instant noodles also solves it, and it somehow gives variety in flavour.

But if the indigenous peoples have local spices, one can set up a farm, though it opens the place up for exploitation, and as the English usage of the word means (the Indonesian word bumbu doesn't have that shade of meaning), it is used dried instead of fresh.

But I'm digressing; in a natural disaster, survival is of primary importance, and as a general accessibility rule of thumb, seasoning and spices would come in a packet, not freshly harvested. And besides, something more easily accessible in the disaster control centre must have accessible food that would make the locals feel less like their means of livelihood has been crippled.