Unlike the French, Southeast Asians Aren’t Scared of Broken Sauces

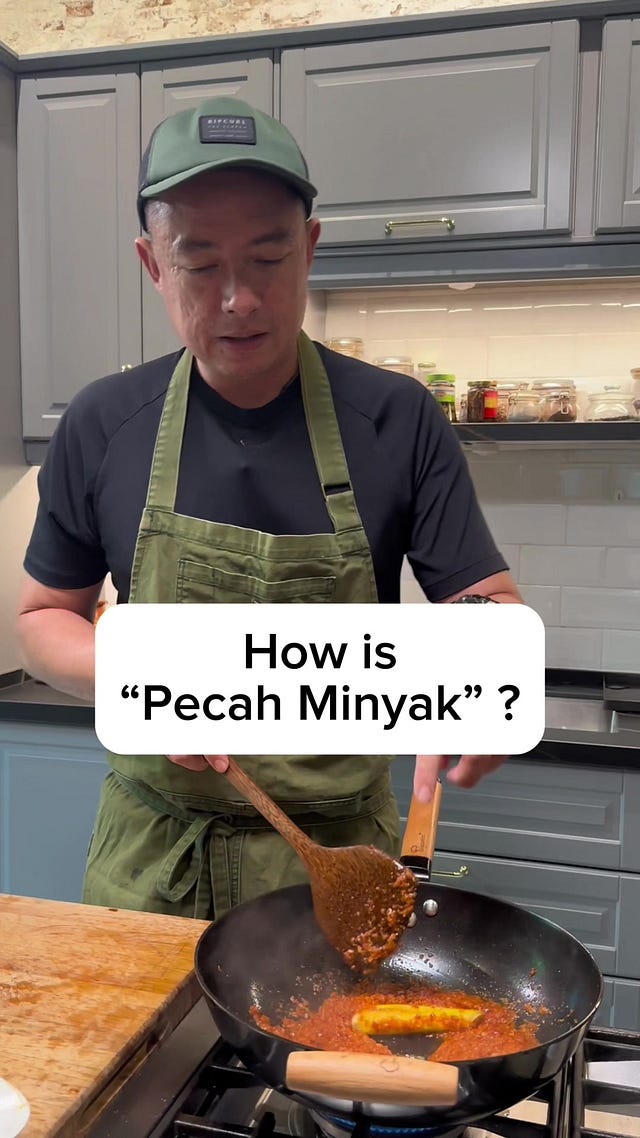

Flavour’s about to go crazy when the oil separates.

Halo and Happy Monday! Welcome to Kepayang. If this is your first time receiving a letter in your inbox, my name is Fabi. I’m the writer and initiator of this newsletter and vibrant community where we talk about all things food, culture, and sustainability. To everyone else: you know the drill.

I’m super excited about today’s newsletter because I think it’s the first time I’m writing about something that isn’t just relatable to Indonesians, but also to many people across the globe, especially my fellow Southeast Asian friends.

Today, I’m talking about a technique that shows up in so many cultures: sautéing. In a lot of Indonesian dishes, sautéing ingredients, especially until the oil separates, is the key to a truly bussin’ dish. The French might see that split oil as a mistake, but we Southeast Asians? We gladly agree to disagree. Enjoy the read!

Kepayang is free for now, so any engagements mean so much to support the platform’s growth. You can subscribe to get the newsletter sent directly to your email, like, comment, and share if you resonate with what I write.

Alternatively, you can buy me a coffee through my PayPal here: https://paypal.me/chalafabia - or if you’re based in Indonesia, you can send your donation through QRIS here (under the name Tamanan). Any amounts are welcomed and will directly contribute to sustaining this platform to cover expenses related to operations, research, writing, and marketing. ☕️

On a random but very normal Tuesday night, I was busy scrolling through YouTube, trying to find something to watch to accompany my dinner. Yes, I’m that iPad kid who won’t start eating unless I find the perfect thing to watch, except that I use my laptop.

I usually go with either a comfort TV show like Abbott Elementary, the iconic food vlogger Ria SW, or a quick documentary about people running their restaurants. That night, I stumbled upon a video by Eater, covering Lita, a Portuguese fine dining spot in New Jersey, USA.

It’s always fascinating to watch what it takes to run a restaurant, but what caught my eye this time was something else.

It wasn’t that Lita was run by chefs, both front and back of house. And though their paella uses a spice base extremely similar to many Indonesian dishes, like garlic, ginger, and shallots, it wasn’t that either.

I paused when David Viana, Lita’s executive chef, told Eater how he made his sofrito.

A sofrito is key to many dishes across cultures, like Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese. Onions, peppers, garlic, tomatoes, all sautéed for hours in a swimming pool of olive oil. What’s interesting is that Viana shared how, after he went to a culinary school and learned classical French techniques, he thought the sofrito his grandmother made, with oil floating on top after hours of sautéing, was done wrong.

Because, you see, in classical French cooking, if oil separates from the rest of the sauce, it’s considered flawed. They call it a broken sauce. (Source: I also went to a French culinary school)

Many years later, Viana eventually realised that his grandmother wasn’t wrong – it was just rooted in a different tradition. And guess who follows that same style of cooking? Southeast Asians.

The reason I paused the first time I heard Viana’s story wasn’t just because of the similarity between Portuguese and Indonesian cooking. It was more about how the practice of sautéing spices, especially until the oil separates from the rest of the ingredients, is so ingrained in my daily cooking that I never considered it a mistake. In fact, it’s somewhat a compulsory step, usually one of the very first that needs to be done properly before I can move on to the next stage.

Let’s say I’m making rendang. The first step is to prep my spices: red chilli, shallots, garlic, ginger, galangal, and a bazillion other things. You can crush them with an ulekan (mortar and pestle), or, since I live in 2025, I use a small spice blender. What you end up with is a smooth, spicy paste called bumbu. These ingredients contain a lot of water, and remember, they’re raw. So you need to sauté the hell out of it before adding anything else to the pot, unless you want your rendang to taste sharp, bitter, and, well… raw.

The act of sautéing with a bit of oil is called menumis in Indonesian, and when I’m menumis bumbu, I always make sure it reaches the point of pecah minyak (oil splitting).

The term pecah minyak is, in my opinion, a far better indicator of doneness when sautéing spices. In many recipes, whether from magazines, blogs, or cooking shows, you’ll often see vague cues like “sauté until fragrant” or “until the paste thickens.” Personally, I find those terms a bit too subjective; everyone’s idea of aroma and texture can differ wildly. Pecah minyak, on the other hand, gives you a clear visual cue that’s hard to misinterpret.

Here’s what actually happens during pecah minyak:

🔥 First, the bumbu starts cooking – you’re heating garlic, shallots, chillies, and friends. They soften and release their aroma. At this stage, the paste may look thick but very wet.

💨 Then, the water begins to evaporate – this is when the sound shifts from bubbling to sizzling. It gets steamy, and the kitchen starts to smell even more amazing.

✨ Finally, pecah minyak – the oil separates and floats, and you’ll see it glistening around the edges. This separation tells you the water has mostly evaporated, and all the flavours have concentrated beautifully.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but I don’t think the term pecah minyak is widely used by Indonesians outside of Sumatra. That’s likely because it may come from Malaysia first and spread through Malay-speaking regions like Banda Aceh, Padang, and Medan.

But whatever term you’re familiar with, a quick desktop research on Southeast Asian recipes will show that we’re all doing the same thing.

Many of our recipes use a ton of fresh spices, so sautéing them properly, especially until the oil splits, is a ritual we all follow. Otherwise, your dish might end up tasting like a raw onion smoothie.

Okay, I lied about it being a “quick” research. I spent two hours in this rabbit hole. So please enjoy the table below and let me know if you liked it.

💡 The table might not show up fully on your email. Try reading it from your browser or the Substack App.

The process of sautéing ingredients isn’t limited to stew-based dishes.

As you can see from the above dishes, many types of dishes involve sautéing ingredients until the oil separates, each for different reasons.

In stew or soup-based dishes like 🇲🇾🇸🇬🇮🇩 Laksa and 🇹🇭 Gaeng Keow Waan, sautéing the spice paste before adding water not only ensures the spices are properly cooked, but also saves time, since heating a small amount of paste is much quicker than heating litres of liquid.

On the other hand, the same technique applies to condiments like 🇻🇳 Sốt Sa Tế, where evaporating moisture is key to concentrating flavour and extending shelf life.

And in the case of 🇵🇭 Latik, oil separation becomes its own cooking technique – as the coconut milk solids fry in the separated oil, it turns into aromatic, crunchy toppings for desserts.

In many Western kitchens (yes, I’m looking at you, France), the sight of oil separating from a sauce might signal a mistake, but in much of Southeast Asia, it’s actually a sign that you’re doing it right. Whether you're making Rendang, Sot Sa Tế, or even Latik, sautéing ingredients until the oil splits is a crucial step that signals flavour development, moisture reduction, and even shelf stability. What might seem like a small visual cue is, in fact, a deeply rooted technique shared across cultures, one that communicates doneness far better than vague instructions ever could.

What other dishes can you think of where you sauté ingredients until the oil splits? Comment down below!

Other contents that I made recently:

💲 Read about how currency exchange might affect your food price: here.

🌱 Read about what kepayang, the plant, truly is: here.

💥 Read about how bakwan sayur is political: here.

✊ Read about why I’m against Indonesia’s agricultural budget cut: here.

🇹🇼 Read about what I ate in Taiwan, but I won’t tell you about the taste: here.

✈️ Read about why I think aeroplane food deserves more love: here.

Watch our recent interview on Kompas TV (Bahasa Indonesia):

If you like today’s newsletter, please like and share it with your friends! Comment down below your thoughts and let me know if you have any other topics you want me to discuss. Until then, I’ll see you in two weeks!

Follow me everywhere:

TikTok: @berusahavegan

Kepayang’s Instagram: @readkepayang

Instagram: @menggemaskan

LinkedIn: Chalafabia Haris

Work with me: readkepayang@gmail.com

Fabi- Jadi bikin laper nih. Sambelnya kayanya enak yah? Tapi bener yah--memang kalau minyaknya mulai 'rivulet' berarti rasanya semuanya akan mulai keluar. Now I'm going to go hunting for sambel. :D -Thalia

showing this to my french boss